Authorial voice. What the heck is it, what's it good for, and how do you get your own?

For writers,

voice is a word we see in critiques and in submission guidelines under What We're Looking For, along with great plots and relatable characters.

For readers,

voice is something to discuss at book club. Ultimately, it's what draws you into a story and keeps you there.

A strong, clear authorial voice is an asset to both writers and readers.

What the heck is it?

In writing, voice is simply the way an author speaks on the page. It's the summation of word choice, syntax, rhythm, and so forth.

What's it good for?

An author's voice is unique to that individual. It's how we distinguish ourselves from other writers.

To illustrate, here are brief passages from two nineteenth century novels:

Example one: Summer passed away in these occupations, and my return to Geneva was fixed for the latter end of autumn; but being delayed by several accidents, winter and snow arrived, the roads were deemed impassable, and my journey was retarded until the ensuing spring. I felt this delay very bitterly, for I longed to see my native town and my beloved friends. (

Frankenstein, by Mary Shelley, first published in 1816)

Example two: The first part of their journey was performed in too melancholy a disposition to be otherwise than tedious and unpleasant. But as they drew towards the end of it, their interest in the appearance of a country to which they were to inhabit overcame their dejection, and a view of Barton Valley as they entered it gave them cheerfulness. (

Sense and Sensibility, by Jane Austen, first published in 1811)

|

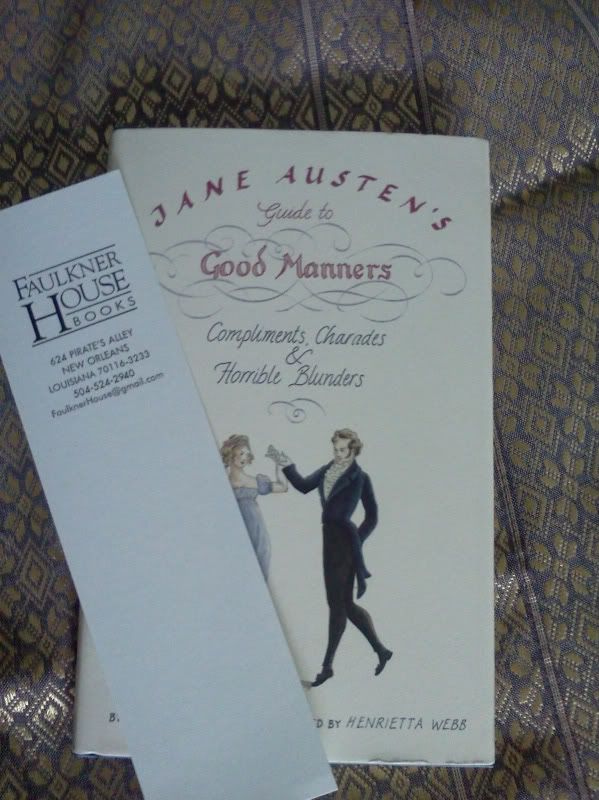

This sweet face authored your earliest

nightmares. |

These passages are similar in both topic and theme (travel, unhappiness), and were published only five years apart. Though there are just two sentences in each passage, Shelley's feels as if there are more, due to the rhythm she creates with punctuation. The first sentence has six phrases separated by commas or semicolon. By contrast, Austen's long sentence (the second one) has only three phrases separated by commas. Shelley's pacing invites the reader's eyes to linger, while Austen's sentences can leave the reader feeling like she needs to catch her breath when she finally reaches a period. Shelley's writing employs plainer words, while Austen tends to the florid.

Despite the similarities in these two brief passages, there are sufficient differences--thanks to each authorial voice--that the two would not be confused as coming from the same writer.

This ability to distinguish oneself from other authors through a strong voice is especially important in genre fiction, such as Romance or Mystery, in which many other writers are telling similar stories. Off the top of my head, I can tell you the stand-out characteristics of a handful of Romance authors--and all those traits relate to voice. Wittiness or concise writing or lyrical prose will appeal to different readers, and keep the ones who appreciate that voice coming back for more.

How to develop a voice of your own

Whether you write a blog, a novel, a poem, or indignant letters to the editor, finding and using your authorial voice is important. How do you do that?

The good news is that, to an extent, your voice comes naturally. You probably never put a lot of thought into your conversational speaking voice. The words you choose to use, whether you inject your speech with sarcasm or humor, these are things that come naturally to you. So, too, will your writing voice.

|

| Try it with a little Ozzy this time. |

Write in the way that feels most comfortable. Don't try to force yourself to be something you aren't. For instance, I adore good snark when I'm reading a piece, but that's just not how I write. I can inject some levity into my own work, but I will never be a humorist. Follow your natural inclinations where they lead.

If you just aren't sure what your voice is like, try out different styles of writing. Maybe your prose is witty like David Sedaris, or stark like Hemingway. Try on various styles and see what fits. Be aware that your authorial voice might be dissimilar from your speaking voice, or they might be nearly identical. The two are different animals, though, so don't try to force your writing voice to be the same as your speaking voice.

Finally, write, write, write. The more you write, the more comfortable you will become with your voice, and the clearer it will be. Just as a young singer may have a sweet singing voice, it takes effort and practice to hone that voice into a clean, unique instrument.