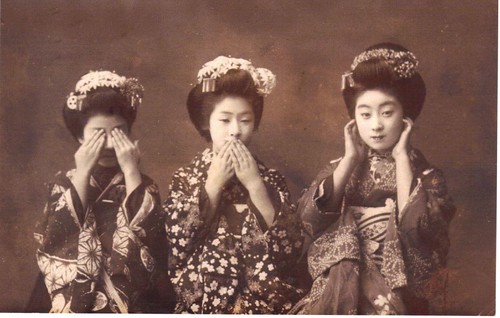

Part two of my blog series loosely inspired by Hear No Evil, See No Evil, Speak No Evil will relate to ladies' fashion during the Regency. This post is a long time coming, as

I touched on Regency menswear quite a while back.

|

| I can't see that drab pelisse! |

"See No Evil" is relevant to this topic, as dressing properly was a full-time occupation for the Regency lady. It was of utmost importance that she present herself as fashionable and attractive--after all, the young lady's job was to marry well. How better to present oneself as manbait than with the right attire?

This will be only the briefest bit of information, as a thorough survey of the topic of Regency fashion could (and has) fill a whole book.

The latter part of the eighteenth and the first twenty years of the nineteenth century were an anomaly of fashion, wedged as they were between eras of flamboyant, Gothic styles. Right around 1800, the crack of women's fashion would be best described as pure Classical. The vertical lines of garments were reminiscent of Greek statuary--indeed, white was a popular color as it hearkened to the marble used to depict ancient goddesses. Long lines conveyed pillars of strength, a sign of courage during this time of war and civil unrest. Hairstyles also emulated classic Greek design--curls piled atop the head, held back with bandeaus and turbans, with loose tendrils framing the face.

|

Miss Dashwood, I think your dress may have

slipped... just a bit... there. |

Now, as we all know, the female form is a ghastly thing--particularly the hip region. You think not liking how your butt looks in those jeans is new? Heavens, no. Women have been utilizing textile trickery to conceal and distract the supposed bad parts of their figures for ages. Literally. Like, since the Bronze Age.

The Regency was no different. I'm sure you're all familiar with the typical Regency dress: High waisted, loose skirts that concealed the hips while revealing just about everything else. Materials were thin and clung to the body to emphasize the shapes of the breasts and legs (But not the hips. Gracious.).

|

Victoria's Secret catalog,

circa 1811. |

A lady of the Regency era had it easy in the undergarment department, compared to her Victorian daughters and granddaughters. Drawers were initially menswear. By the early 1800's, women had started to borrow the idea for their own wardrobes, but they weren't in common use until later in the century. At the time of the Regency, many regarded wearing anything masculine as vulgar. Much better to do without anything down there but the breeze. Ahem. So a Regency lady may or may not don drawers. The next layer of clothing would be the chemise or shift (which functioned like a modern slip), topped with a set of short, soft stays and perhaps a single petticoat, depending on the dress she planned to wear. Undergarments were white, to convey the wearer's purity of heart and mind (and body, you naughty rake!).

Muslin was the fabric of choice for the masses. It was inexpensive, and had a marvelous way of displaying a woman's anatomy just so. It was widely used for undergarments and a whole array of dresses used from morning to night. The most daring, fast women might dampen their chemise so the muslin skirt of the dress would cling closely to the legs (and Catholic schoolgirls thought rolling their waistbands was innovative. Pfft.).

|

| You know you want to wear that turban. |

Even though the Regency lady was happy to show off her curves (except the hips--puke), do not think she had no standards of modesty. A proper lady always covered her head when she left the house, and took a covering like a shawl, pelisse, or spencer along. The bosom only came out to play at night, although day dresses still emphasized shape. Gloves were absolutely

de rigeur, both inside and out. A lady took her gloves off to eat, then put them on again when the meal was over. Can't go about with our fingers dangling loose like a common hussy now, can we?

If the form of the Regency woman's dress was rather simple, they found a lot of room for fun in the color department. Especially when it came to evening wear, the brighter, the better! Jewel tones and primary colors were popular, and there's good reasoning behind this. The Regency ballroom or dining room was illuminated only by candlelight, with the occasional oil lamp tossed in for variety. The dim, yellow light washed out pale colors. Only the boldest shades stood up to contemporary luminary shortcomings. White was a popular choice for gowns, too, and was mandatory for a young lady's debut ball. Satins and silks reflected light nicely. Metal adornments like spangles sewed onto skirts and turbans, silver and gold thread worked into lace, and jewelry added sparkle to catch a gentleman's eye and show your rivals you mean business.

I hope you've enjoyed this very brief foray into Regency women's fashion! There is so much more to explore. Maybe we'll revisit the topic again in a future post.